The U.S. Supreme Court handed down a major ruling on affirmative action Thursday, rejecting the use of race as a factor in college admissions as a violation of the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

In a 6-3 decision, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the majority opinion that, “A benefit to a student who overcame racial discrimination, for example, must be tied to that student’s courage and determination.”

“Or a benefit to a student whose heritage or culture motivated him or her to assume a leadership role or attain a particular goal must be tied to that student’s unique ability to contribute to the university. In other words, the student must be treated based on his or her experiences as an individual—not on the basis of race,” the opinion reads.

“Many universities have for too long done just the opposite. And in doing so, they have concluded, wrongly, that the touchstone of an individual’s identity is not challenges bested, skills built, or lessons learned but the color of their skin. Our constitutional history does not tolerate that choice,” the opinion states.

Justice Roberts was joined by Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett.

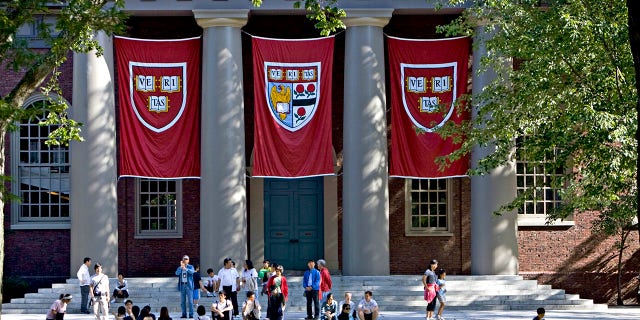

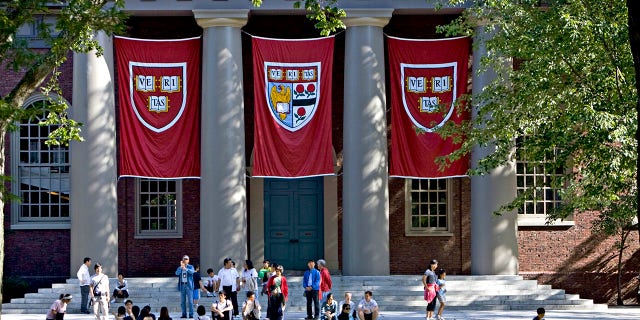

Harvard banners hang outside Memorial Church on the Harvard University campus in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on Friday, Sept. 4, 2009. The Supreme Court ruled in affirmative action cases, including one over Harvard’s admissions practices. (Photo by Michael Fein/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote the main dissent, joined by Justices Elena Kagan and in part by Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, who recused herself from the Harvard case due to her previous role on Harvard’s Board of Overseers.

President Biden is expected to deliver remarks on the decision at 12:30 p.m. on Thursday.

The justices decided two separate legal challenges over just how Harvard University – a private institution – and the University of North Carolina – a public one – decide who fills their classrooms.

These prominent schools say their standards have a larger societal goal, one endorsed for decades by the courts: to promote a robust, intellectually diverse campus for future leaders.

But a coalition of Asian American students says the criteria discriminated with a “racial penalty” – holding them to a selectively higher standard than many Black and Hispanic students.

Student activist group Students for Fair Admissions brought cases against both Harvard and University of North Carolina. The group initially sued Harvard College in 2014 for violating Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, which “prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin in any program or activity that receives Federal funds or other Federal financial assistance.”

The complaint against Harvard alleged that the school’s practices penalized Asian American students, and that they failed to employ race-neutral practices. The North Carolina case raised the issue of whether the university could reject the use of non-race-based practices without showing that they would bring down the school’s academic quality or negatively impact the benefits gained from campus diversity.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit had ruled in Harvard’s favor, upholding the outcome of a district court bench trial. The district court said that the evidence against Harvard was inconclusive and that “the observed discrimination” affected only a small pool of Asian American students. It ruled that SFFA did not have standing in the case.

In the UNC case, a federal district court ruled in the school’s favor, saying that its admissions practices withstood strict scrutiny.

Roberts said in his majority opinion that both admissions programs at Harvard and UNC “lack sufficiently focused and measurable objectives warranting the use of race, unavoidably employ race in a negative manner, involve racial stereotyping, and lack meaningful end points.”

“We have never permitted admissions programs to work in that way, and we will not do so today,” he said.

The Supreme Court handed down a new ruling on affirmative action. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite, File)

Justice Clarence Thomas, while agreeing with the majority opinion, wrote a separate concurrence with his own thoughts.

The decision, he said, “sees the universities’ admissions policies for what they are: rudderless, race-based preferences designed to ensure a particular racial mix in their entering classes. Those policies fly in the face of our colorblind Constitution and our Nation’s equality ideal. In short, they are plainly—and boldly—unconstitutional.”

“While I am painfully aware of the social and economic ravages which have befallen my race and all who suffer discrimination, I hold out enduring hope that this country will live up to its principles so clearly enunciated in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States: that all men are created equal, are equal citizens, and must be treated equally before the law,” Thomas wrote.

The affirmative action cases gave rise to one of the most spirited court debates to occur within the Supreme Court building this past term, with Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito grilling Harvard’s lawyer, Seth Waxman.

Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts got into a heated exchange with Harvard’s lawyers regarding affirmative action. (Julia Nikhinson-Pool/Getty Images)

Alito pressed Waxman on why it is that Asian American students regularly receive lower personal scores on their applications than other races. Waxman talked around the justice’s questions, causing Alito to get frustrated with the lawyer.

“I still haven’t heard any explanation for the disparity between the personal scores that are given to Asians,” Alito said.

Waxman then got into a tense back-and-forth with Roberts. The justice asked why Waxman was downplaying race as a factor in admissions decisions, when according to Roberts it must have some impact, or else it would not be included.

Waxman admitted that race was decisive “for some highly qualified applicants,” just like “being … an oboe player in a year in which the Harvard-Radcliffe Orchestra needs an oboe player.”

“We did not fight a civil war about oboe players,” Roberts shot back. “We did fight a civil war to eliminate racial discrimination.”

In 2003, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor was the “swing” – or deciding – vote in a landmark Supreme Court case over race.

While upholding the University of Michigan’s affirmative action policies for minority law school applicants, the court majority led by O’Connor offered this caveat: “We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today.”

Fast-forward 19 years, and a 6-3 conservative court majority has now blocked colleges and universities from using race as part of the competitive admissions process.